Ruling out tax rises undermines Sunak's and Starmer's credibility on public services

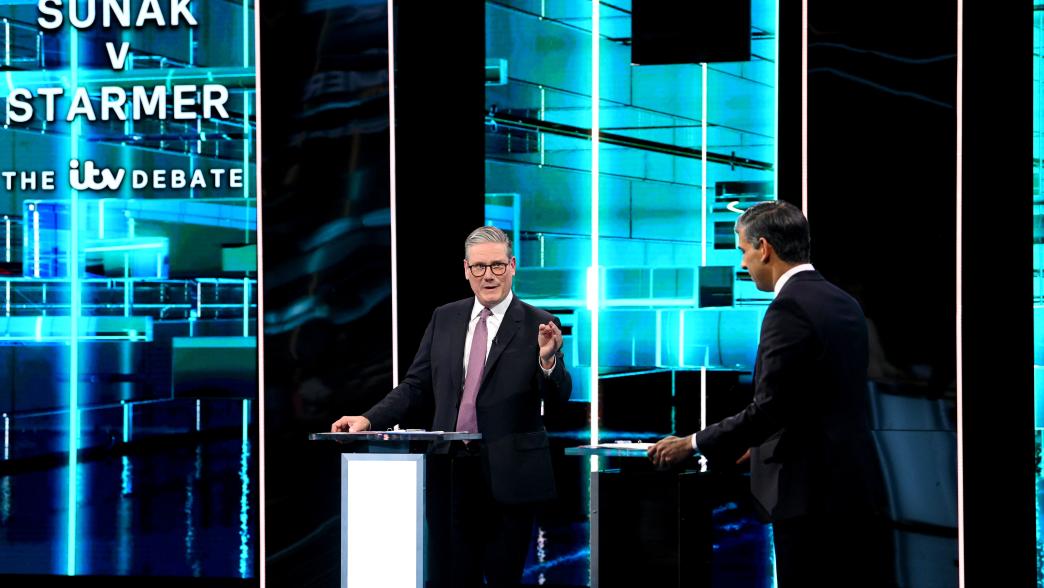

Rishi Sunak and Keir Starmer are making tax pledges that limit their public spending options.

Pledges not to raise the main taxes have become a prominent feature of UK elections but such commitments unhelpfully limit any future government’s room for manoeuvre in addressing struggling public services, says Gemma Tetlow

Promising not to raise the UK’s main taxes has become a common theme of parties’ pitches to the electorate and this election is turning out to be no different.

The Conservatives have ruled out increasing income tax, National Insurance contributions (NICs) and VAT, which between them account for 64% of all UK tax revenues. Labour have in addition ruled out raising the main rate of corporation tax – adding that into the mix covers 74% of all tax revenues.

There are apparently good political reasons to make such promises, an it is an article of faith that voters do not like tax rises. But recent polling suggests they are just as likely to say that they would like government to increase spending on public services, even if it mean paying more tax, as they are to say that they would prefer government to cut the taxes they pay, even if it meant lower public services spending.

However, ruling out the possibility of raising any of the main, most broad based and least distorting taxes seriously undermines the credibility of the parties’ promises to improve public services, and by limiting their room for manoeuvre will make it more difficult for whoever forms the next government to govern well.

The main parties are signed up to implausible spending plans

At the same time as they have ruled out increasing any of the main taxes, the main parties are also promising to address the chronic problems evident in many public services. But this is hard to square with current government spending plans for the next parliament which imply large real terms cuts to funding for many public services, such as the police, courts and prisons. Despite high profile (and questionable) claims that Labour has made additional spending commitments, Labour has broadly signed up to the government’s headline spending plans.

Unfortunately, while elections have a tendency of forcing parties into firm commitments on tax, there is no such pressure to spell out in full detail their plans for spending on individual public services. Yet the promises on tax (coupled with promises to limit borrowing and debt) imply tight limits on public spending. It is not plausible to think that the next government can address existing major problems in public services without spending more than is currently pencilled in – or announcing cuts to some areas of services or social security.

The tax pledges seriously undermine the credibility of their public service aspirations: the parties are presumably hoping the electorate will not notice. But recent polling, showing that more than half of people expect tax rises under either a Labour or Conservative government, suggest that voters are not so easily fooled.

The future chancellor will come to regret these tax pledges

There are still ways that the parties could improve the tax system – and raise more money if they want to. Many smaller taxes – such as capital gains tax, inheritance tax and stamp duty land tax – are not covered by the pledges so far. There are opportunities to reform those to reduce economic distortions and complexity in the tax system, if the next chancellor wants to seize them.

Doing that will be easier if the winning party’s manifesto makes a clear case for action to give the future government a mandate. Achieving meaningful tax reform is difficult but not impossible. Any aspiring tax reforming chancellor will need clear objectives for what he or she wants to achieve, a strategy for delivering it and to avoid the temptation to tinker along the way. That strategy should consider how measures can be packaged, how tax measures complement other policies, and how a coalition of support can be built.

The promises all the main UK political parties have now made not to raise the rates of the main taxes fundamentally undermines the credibility of their promises on public services. Governing well requires making difficult trade-offs, including between a desire for low taxes and a desire for a range of high quality public services. Ruling out tax rises implies a choice about what spending can be afforded. Such choices should not be made lightly and the electorate should understand the implications.

- Political party

- Conservative Labour

- Administration

- Sunak government

- Department

- HM Treasury

- Public figures

- Jeremy Hunt Rishi Sunak Keir Starmer

- Publisher

- Institute for Government