The precarious state of the state: Devolution

Progress has been made on transferring power away from London, but there is more to do.

This year Wales and Scotland marked 25 years of devolution, settlements which have deepened over time; Northern Ireland also saw the formation of a power-sharing executive under the Belfast Agreement a quarter of a century ago and has accrued new powers since.

But despite progress on devolution, the picture is mixed across the country and the UK overall remains a highly centralised state. Devolution to parts of England has been much more recent but has progressed quickly: as of May 2024 there are 12 metro mayors who are important players responsible for significant powers and budgets. As this landscape evolves, the next government will need to define a new vision for intergovernmental relations to deliver against its policy objectives and ensure coherence across the union.

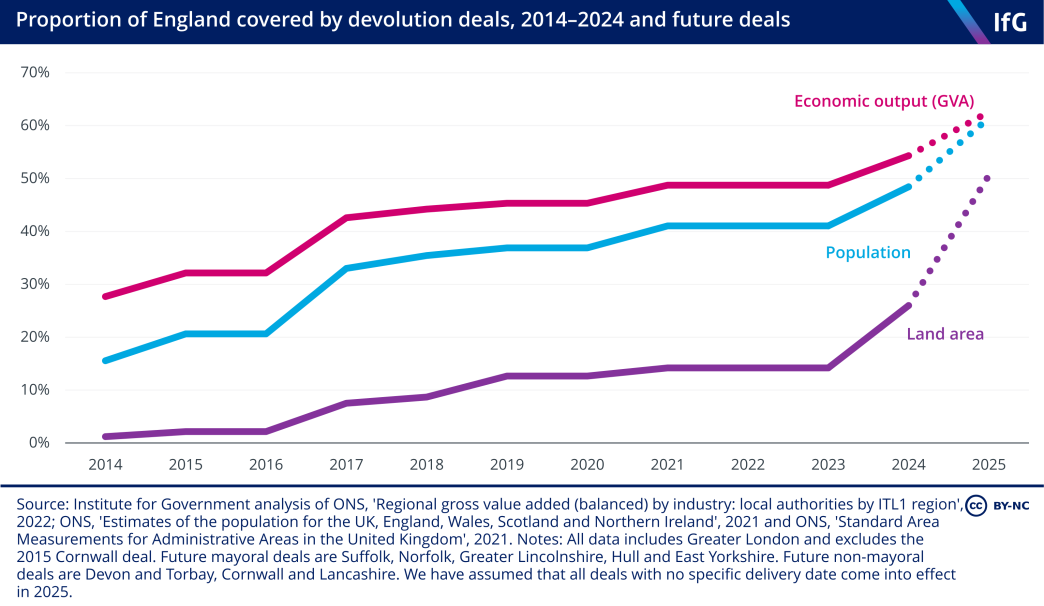

Nearly half of England’s population is now represented by a metro mayor

Through a series of bespoke ‘devolution deals’ Whitehall has devolved powers and funding to metro mayors who chair combined authorities, made up of constituent local authorities. 53 We include the Mayor of London as a ‘Metro Mayor’, but this role was created through the Greater London Authority Act 1999 rather than as part of a devolution deal, and the mayor does not chair a combined authority. Since the first devolution deal in 2014 there has been both a broadening and deepening of devolution. Metro mayors were elected in six areas in 2017, with three more by 2021. There are now 12 in post, covering almost half of England’s population and more than half of the country’s economic output. Four further mayoral deals and three non-mayoral deals have been agreed with the current government. 54 The four deals with mayoral powers are with Hull and East Riding, Greater Lincolnshire, Norfolk and Suffolk (the latter two will have ‘directly elected leaders’ rather than mayors), which were due to come into force in 2025. The non-mayoral deals are with Cornwall, Lancashire, and Devon and Torbay. Three further non-mayoral devolution framework agreements were announced for Surrey, Buckinghamshire and Warwickshire in the 2024 Spring Budget. The statutory instruments for these deals were not laid before parliament was dissolved.

Despite progress, many areas – including key urban areas – still lack a devolution deal

Despite this progress, there is still further to go. Different regions are at different stages of their journey; deals vary in scope and effectiveness, English devolution continues to have an uncertain constitutional status, and some places have been left out entirely. 58 Akash Paun et al, A new deal for England: How the next government should complete the job of English devolution, Institute for Government, 2024, p. 4, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/next-government-complete-english-devolution. The current map overlooks many large urban centres such as Leicester, Southampton and Stoke. 59 At present, nine of the 25 largest ‘primary urban areas’ (PUAs) (based on 2021 Census data) are without devolution, including Leicester, Portsmouth, Northampton, Bournemouth, Southampton, Stoke, Southend, Reading and Brighton. Source: Figure 1 in Quinio V and Rodrigues G, ‘What do the first Census 2021 results say about the state of urban Britain?’, blog, Centre for Cities, 1 July 2022, retrieved 17 April 2024, www.centreforcities.org/blog/what-do-the-first-census-2021-results-say-about-the-state-of-urban-britain.

With the ‘low hanging fruit’ of places with obvious, coherent geography and a high level of local support for devolution picked, hard decisions remain on how to continue the process. 60 Akash Paun, ‘The 2023 autumn statement marks a step forward on devolution – but the job is far from complete’, Institute for Government, 23 November 2023, retrieved 29 May 2024, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/comment/autumn-statement-devolution-deals. Yet these remaining urban centres are critical to any government seeking economic growth across the country. In our report ‘A New Deal for England’ we argue that a realistic target is for 85% of England’s population to have a devolution deal by the end of the next parliament.

Cities outside London – including Manchester and Birmingham – have worse economic performance than international comparators

Nationally, productivity measured in terms of gross value added per hour worked is unequally distributed, with London outperforming the national average. The UK’s other major urban centres also lag behind by a larger margin than their equivalents in comparator countries like Germany or Spain. 63 Resolution Foundation & Centre for Economic Performance, LSE, Ending Stagnation: A New Economic Strategy for Britain, Resolution Foundation, 2023, p. 134, economy2030.resolutionfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/Ending-stagnation-final-report.pdf. Some figures are particularly striking: productivity levels in Greater Manchester and the West Midlands are more than 10% below the national average, despite Birmingham and Manchester being among the UK’s largest cities by population.

Mayors now have responsibility for important policy levers to address these challenges, such as skills policy – previous Institute for Government work has shown that the skills mismatch between the skills demanded by employers and the skills the workers have is a drag on UK productivity. 64 Thomas Pope, Grant Dalton, Maelyne Coggins, How can devolution deliver regional growth in England?, Institute for Government, 2023, p. 27, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/sites/default/files/2023-05/devolution-and-regional-growth-england.pdf.

Mayors play an increasingly important policy role and will be crucial for delivering the next government’s objectives

The current devolution framework only offers certain powers and funding to those areas which take on a mayor. These metro mayors have significant devolved policy powers and budgetary responsibility; they are collectively responsible for approximately £30bn of public sector spending. Though local factors have shaped how deals were negotiated, there are a set of core powers across the mayors including responsibilities for housing, skills and a 30-year investment fund. They can also establish mayoral development corporations, with powers over planning and development, and can impose a precept on council tax to fund specific projects. Some mayors hold additional powers, for example in health and, where boundaries align, police and crime commissioner powers.

Since 2022, the government has also sought to deepen devolution powers through the introduction of ‘trailblazer’ deals to Greater Manchester and the West Midlands. When fully implemented, the trailblazer devolution model will include a new ‘single settlement’ for these areas, which will provide greater flexibility for spending to be prioritised in line with local needs. At the moment key areas such as employment support and strategic spatial planning which evidence shows would support regional growth are missing from these existing trailblazers. 68 Thomas Pope, Grant Dalton, Maelyne Coggins, How can devolution deliver regional growth in England?, Institute for Government, 2023, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/sites/default/files/2023-05/devolution-and-regional-growth-england.pdf. In 2023, the government also introduced a new level 4 deal for areas 69 In March 2024 the government confirmed that West Yorkshire, Liverpool City Region and South Yorkshire were eligible for level 4 devolution, and that they would work with those areas to implement agreements. The government also confirmed that they would work with the West Midlands to implement level 4 devolution as well as their trailblazer deal, and agreed a ‘deeper devolution deal’ with the North East that was underpinned by the level 4 framework. designed as a stepping stone towards the single-settlement trailblazer deals. 70 Department for Levelling Up, Housing, and Communities, ‘Technical paper on Level 4 devolution framework’, Department for Levelling Up, Housing, and Communities, 22 November 2023, retrieved 28 May 2024, www.gov.uk/government/publications/technical-paper-on-level-4-devolution-framework/technical-paper-on-level-4-devolution-framework.

General election 2024

The next UK general election will be held on Thursday 4 July. Our analysis, explainers and events explore what happens before and during an election, how political parties and the civil service prepare for the outcome and what it means for government.

Find out more

A new group of largely Labour mayors will define relations with the next government

At the last general election in 2019, there was an almost equal split of four Conservative mayors and five Labour mayors. After the May 2024 local elections 11 of the 12 are Labour, with just a single Conservative mayor. As vocal champions for their regions, these mayors could form a powerful coalition – asking for more powers and investment through the UK Mayors group.

At times in recent years, Labour mayors have felt that their party affiliation limited access to cabinet ministers and additional funding, hindering their potential to work with the government. 73 At times in recent years, Labour mayors have felt that their party affiliation limited access to cabinet ministers and additional funding, hindering their potential to work with the government. That said, it is not the case that mayors must agree with a government of the same party. Conservative mayors have also shown a willingness to challenge their national leadership, such as when then West Midlands mayor Andy Street publicly challenged Sunak’s cancellation of the northern half of HS2. And Labour mayors have stated that they would ‘stand up’ to a potential Labour government if required. That said, it is not the case that mayors must agree with a government of the same party. Conservative mayors have also shown a willingness to challenge their national leadership, such as when then West Midlands mayor Andy Street publicly challenged Sunak’s cancellation of the northern half of HS2. And Labour mayors have stated that they would ‘stand up’ to a potential Labour government if required. 74 Steve Robson and Hugo Gye, ‘‘We will stand up to Starmer,’ Labour mayors warn’, iNews, 27 May 2024, retrieved 28 May 2024, inews.co.uk/news/politics/stand-up-starmer-labour-mayors-3045649.

Whichever party wins the general election, the prime minister and Whitehall will need to set the right tone, and build central relationships early. New structures, such as minister-mayoral committees, will be needed to ensure all mayors are able to work as strategic partners of government regardless of party affiliation.

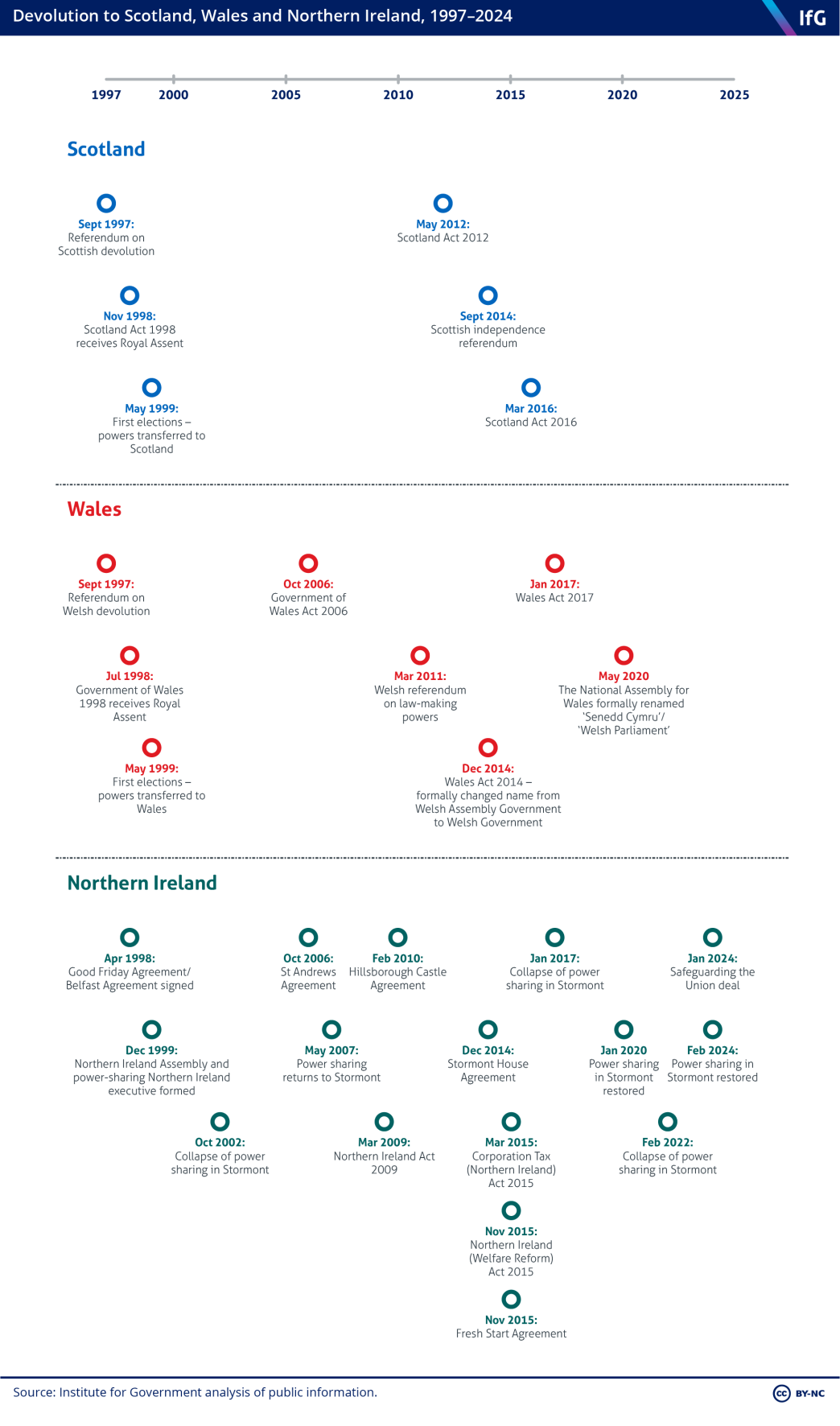

Further powers and funding have been devolved to Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland in the past 14 years

Devolution has evolved since 1999 following appetite for deeper powers. Scotland has gained increased tax and social security powers, Northern Ireland powers over policing and justice, and Wales full legislative powers in 2011 as well as a wider devolved range of policy areas. There is a desire within some devolved governments for further powers to be devolved.

The amount spent by the UK government across the nations varies according to a combination of historic agreements and the Barnett Formula. In 2023/24 the planned Barnett Block grant amounted to £31bn in Scotland, £19bn in Wales and £16bn in Northern Ireland. 78 HM Treasury, Block Grant Transparency: Jul 2023, 18 August 2023, retrieved 5 June 2024, www.gov.uk/government/publications/block-grant-transparency-july-2023 This reflects differences in population size as well as the range of devolved public services in each nation.

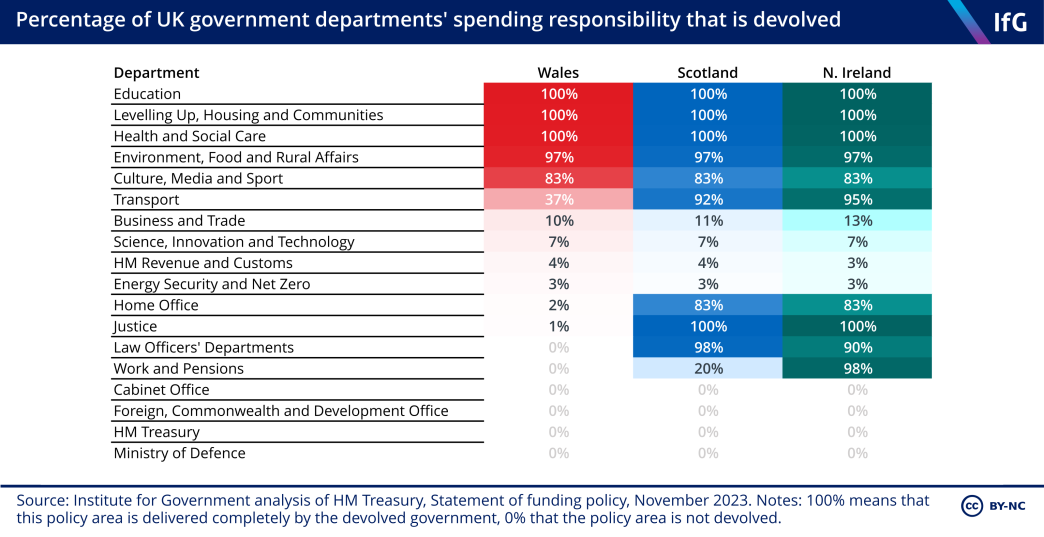

There are a common core set of devolved policy and spending responsibilities across the devolution settlements, such as education, and health and social care. However, there are contrasting responsibilities across other policy areas, such as justice and transport. This complex landscape can complicate policy making, leading to disagreement as well as confusion over what decisions can be made and at what level.

Through initiatives such as the annual civil service ‘devolution training week’ devolution awareness has been improved across Whitehall. 79 Institute for Government, (2024), Written evidence from the Institute for Government (DWC21). Available at committees.parliament.uk/writtenevidence/127350/pdf/ accessed on 4 June 2024. However, Whitehall’s devolution capability has been a source of frustration, 80 Akash Paun et al, Ministers reflect on devolution: Lessons from 20 years of Scottish and Welsh devolution, Institute for Government, March 2019, p. 27, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/sites/default/files/publications/Ministers-reflect-on-devolution-WEB.pdf. and there is a continual need to monitor devolution capability to ensure that central government can coordinate across policy areas.

The future of the Union and devolution settlements for the nations remains a live debate

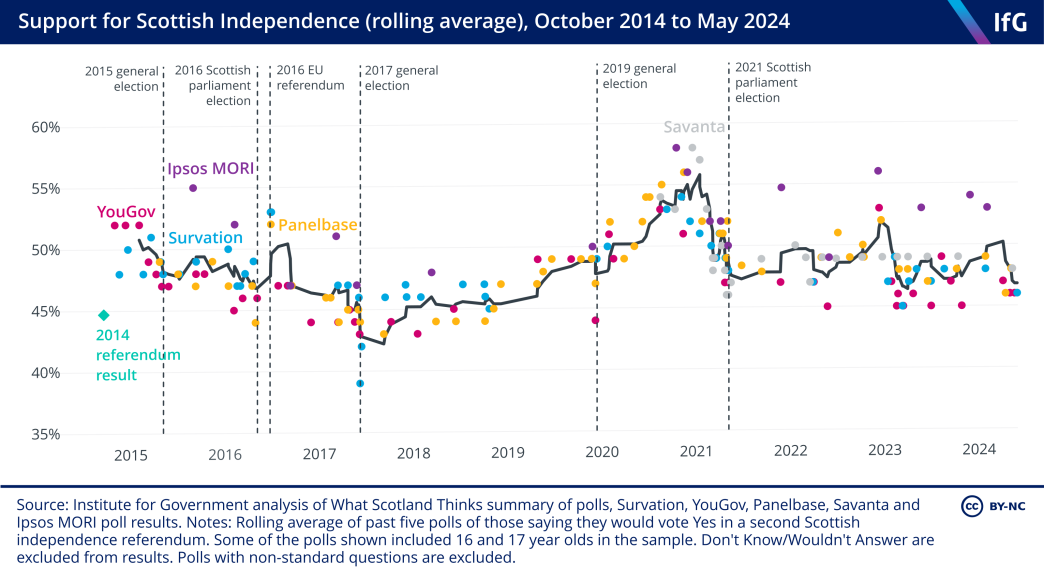

Almost 10 years on from the Scottish independence referendum – which saw 55% of voters choose to remain within the union on an almost 85% turnout – independence remains a divisive topic. Polls have shown a higher level of support for independence since the 2014 referendum, though for the majority of the time the average has been below 50%.

During this period the Scottish National Party continued to have electoral success and has been the party with the most seats in Holyrood since 2007. It also secured the largest number of Scottish MPs in Westminster since 2015. 83 Richard Cracknell, Elise Uberoi, Matthew Burton, UK Election Statistics: 1918-2023, A Long Century of Elections, House of Commons Library, 2023, p. 25, researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/CBP-7529/CBP-7529.pdf. However, recent controversy including the collapse of the SNP and Green Party cooperation agreement, the recent churn of party leaders, and a decline in opinion polling ratings suggest less certain electoral prospects for the party.

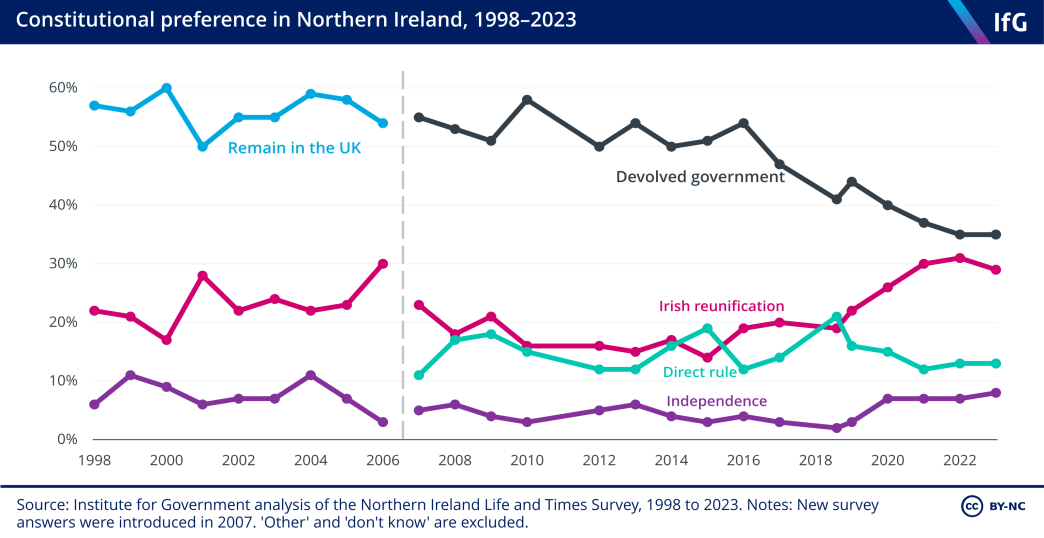

Following the collapse of power sharing in Northern Ireland in 2017 there was rising support for Irish Reunification. UK law provides for the possibility of a border poll if it seems likely that a majority of voters in Northern Ireland would vote for reunification. As of 2022 almost a third of those surveyed preferred Irish reunification, coming close to the level of support for devolved government.

In 2024 Northern Ireland saw for the first time a government headed by a first minister from Sinn Fein after the party won the most seats in the Northern Ireland assembly election in 2022. Sinn Fein advocates for a united Ireland. This led to nationalist affiliated parties saying they expect there to be a border poll by the end of the decade. In part the result for Sinn Fein was linked to a decline in support for the DUP in an election where the Alliance Party – a non-aligned party – surged. If the Alliance Party became the second largest party in the Northern Ireland Assembly this would require constitutional reform to grant them the deputy first minister post.

In Wales, the Independent Commission on the Constitutional Future of Wales was set up as part of the cooperation agreement between Labour and Plaid Cymru in 2021. 84 This agreement was cancelled by Plaid Cymru in May 2024 It outlined and assessed three “viable option[s] for the governance of Wales in the long term”: enhanced devolution, a federal UK structure and Welsh independence. These recommendations are unlikely to be implemented in full as it would require UK parliament legislation and the UK parties have not given unequivocal support. Yet it illustrates the continuing appetite to reopen the Welsh devolution settlement.

Relations between the nations have been strained

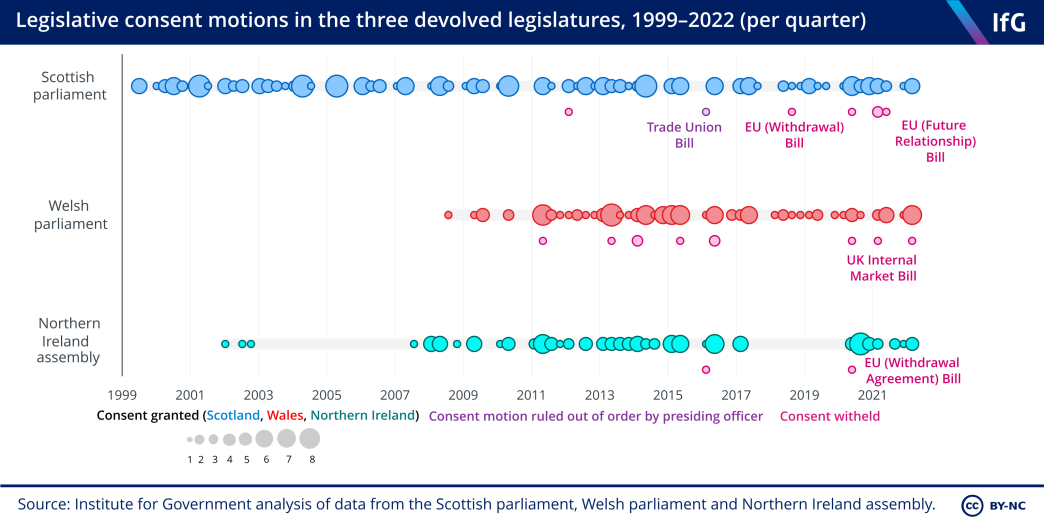

Within the agreed processes for intergovernmental consultation, the three devolved governments have withheld consent on at least 18 UK bills 88 More than one government may have withheld consent for a UK Bill, meaning the number of times consent was withheld in total would be higher across the three devolved governments. since the last general election. Withholding consent has been more frequent since Brexit. The Sewel convention sets out that UK parliament will “not normally legislate with regard to devolved matters except with the agreement of the devolved legislature”. 89 HM Government, Memorandum of Understanding and Supplementary Agreements Between the United Kingdom Government, the Scottish Ministers, the Welsh Ministers, and the Northern Ireland Executive Committee [The Memorandum of Understanding], 2013, assets.publishing.service. gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/316157/MoU_between_the_ UK_and_the_Devolved_Administrations.pdf. However, as a convention, it is not binding, and its operation relies on trust, as well as open communication and compromise. 90 Jess Sargeant, ‘The Sewel Convention has been broken by Brexit – reform is now urgent’, Institute for Government, 12 January 2020, retrieved 30 April 2024, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/article/comment/sewel-convention-has-been-broken-brexit-reform-now-urgent.

The UK government usually discusses bills privately with devolved governments, working together to ensure that concerns addressed before devolved governments publicly give or withhold consent. An increase in consent being withheld shows a clear need for greater coordination and communication between the governments.

Brexit deepened tensions between the governments and these deteriorated further with the UK Internal Market Act

The UK government excluded the devolved administrations from any meaningful say in the negotiations, and the 2020 European Union Withdrawal Agreement Bill passed despite all devolved governments withholding consent. In 2020 the UK government passed the UK Internal Market (UKIM) Act, which aimed at ensuring no new barriers would be created for business trading across Great Britain. This legislation was opposed by the Scottish and Welsh governments (with Wales launching a judicial review into it), 92 Josh Hayman, ‘The UK Internal Market Act: How does it impact Welsh law?’ Ymchwil y Senedd, Senedd Research, 20 February 2023, retrieved 4 June 2024, research.senedd.wales/research-articles/the-uk-internal-market-act-how-does-it-impact-welsh-law/. both arguing that it was a Westminster power grab because it restricted their ability to exclude goods that did not meet their regulations from their markets, which they saw as undermining the devolution settlement.

Additionally, the exceptional arrangements agreed as part of the UK’s exit from the EU, first in the form of the Northern Ireland protocol and then the Windsor Framework, also led to tensions between unionists and the UK government causing a breakdown in power sharing in Northern Ireland. This was only resolved through a new deal reached by the government with the DUP earlier this year which allowed power sharing to be restored.

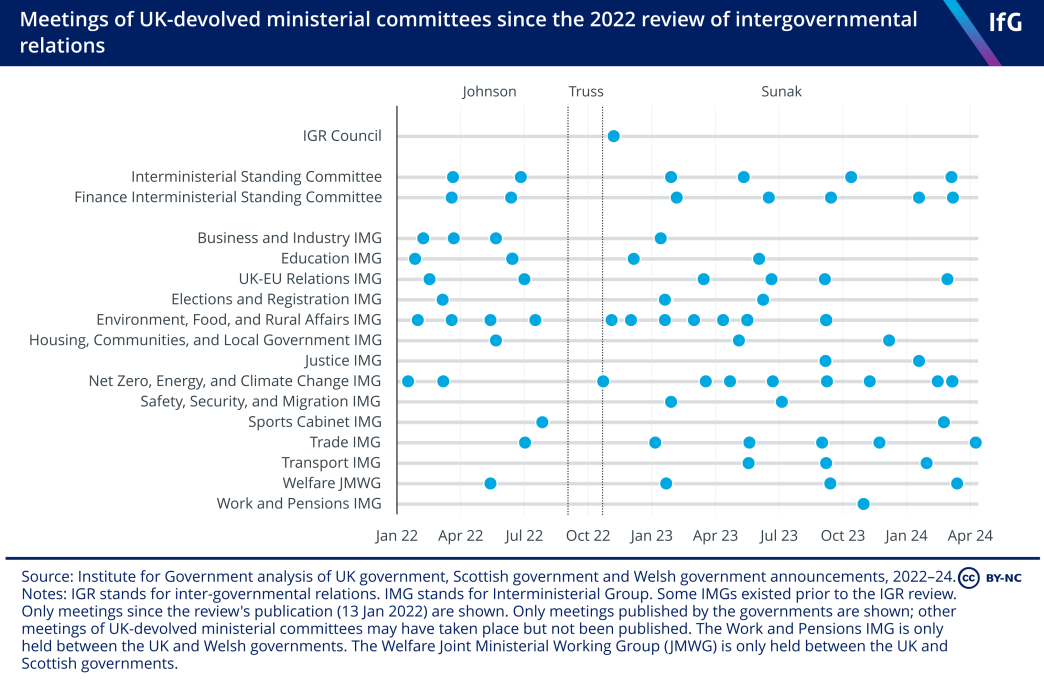

The UK government has an opportunity to reset relations

In 2022, a new intergovernmental framework was introduced, superseding the previous one – the Joint Ministerial Committee – that had been established in 1999 but had largely ceased to function. This system had been criticised for its lack of transparency, irregular meeting schedules, and weak dispute resolution protocol. Responding to the pandemic had also presented new challenges for intergovernmental working, which had already been strained by Brexit. Relations have also suffered from a high turnover of ministers in Whitehall. 97 Institute for Government, (2024), Written evidence from the Institute for Government (DWC21). Available at committees.parliament.uk/writtenevidence/127350/pdf/ accessed on 4 June 2024.

Both the Welsh and Scottish governments have expressed that while the structures and mechanisms offer the opportunity for improved cooperation and working, the experience so far has been mixed. 98 Welsh Government, ‘Inter-Institutional relations agreement between the Senedd and the Welsh Government: report on intergovernmental relations covering the period 2021 to 2023’, 18 July 2023, retrieved 4 June 2024, www.gov.wales/sites/default/files/pdf-versions/2023/7/2/1689667364/providing-inter-governmental-information-to-the-senedd-report-2021-to-2023.pdf The framework still relies on the impetus and enthusiasm of the UK government, and with instability in the UK government in recent years, implementation has been slow. 99 Adam Cooke, ‘Two years on, has the review of intergovernmental relations led to “ambitious and effective working?”, Ymchwil y Senedd, Senedd Research, 1 February 2024, retrieved 4 June 2024, research.senedd.wales/research-articles/two-years-on-has-the-review-of-intergovernmental-relations-led-to-ambitious-and-effective-working/.

This year has seen changes in leadership across all three devolved nations, 100 See Briony Allen, ‘Welsh Labour leadership election 2024: How did Wales choose its new first minister?’, Institute for Government, 21 March 2024, retrieved 5 June 2024, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/explainer/welsh-labour-leadership; Akash Paun, Duncan Henderson, and Briony Allen, ‘SNP leadership: How was John Swinney selected as first minister of Scotland?’, Institute for Government, 9 May 2024, retrieved 5 June 2024, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/explainer/snp-leadership-first-minister; Jill Rutter, and Matthew Fright, ‘Government deal with the DUP to restore power sharing in Northern Ireland’, Institute for Government, 1 February 2024, retrieved 5 June 2024, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/explainer/government-deal-dup-restore-power-sharing-northern-ireland. offering a clear opportunity to reset the relationship between the nations. Whoever wins the next election will face a relatively new set of first ministers and other ministers to engage with and has the opportunity – through their tone and actions – to redefine intergovernmental relations.

- Topic

- Devolution

- Political party

- Conservative Labour Scottish National Party Democratic Unionist Party Sinn Féin

- Position

- Metro mayor First minister of Scotland First minister of Northern Ireland First minister of Wales

- Devolved administration

- Scottish government Welsh government Northern Ireland executive

- Publisher

- Institute for Government